Category: Civil

-

Danganan v. Guardian Protective Services: UTPCPL violation need not be in Pennsylvania

Written by

on

The Pennsylvania Supreme Court ruled unanimously in Danganan v. Guardian Protective Services that a violation of the Unfair Trade Practices Consumer Protection Law need not have occurred in Pennsylvania to…

-

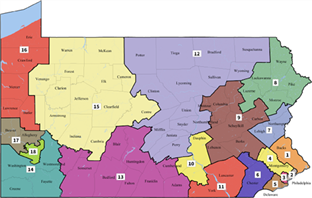

League of Women Voters v. Commonwealth: The “Free and Equal Elections” Clause Prohibits Gerrymandering

Written by

on

EDIT: The map has been released as promised by the Court, along with a brief opinion on February 19, re-outlining the views of the Court. We have included it here…

-

Shearer v. Hafer: Interlocutory Appeal unavailable for civil pretrial dispute over right to counsel at psychological examination

Written by

on

In Shearer v. Hafer, the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania rules 6-1 that an interlocutory appeal was not appropriate in a pretrial discovery dispute over whether a plaintiff has the right…

-

Scarnati v. Wolf: Press Releases aren’t “Proclamations”

Written by

on

In Scarnati v. Wolf, the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania rules 6-1 that a press release does not satisfy the Pennsylvania Constitution’s requirement of veto by proclamation under Article IV, Section…

-

In re 2014 Allegheny County Grand Jury: Mootness ruling must be based on facts

Written by

on

In an unusually brief, unanimous opinion, Chief Justice Saylor ruled that the Superior Court erred in finding a dispute between two parties moot where the facts of record did not…

-

Miller v. County of Centre: District Attorneys are not “Judicial Agencies” exempt from Right to Know disclosure requirements

Written by

on

Right to Know (RTK) requests by several defense attorneys in Centre County (home of Mount Nittany) revealed communications between DA Stacy Parks Miller and judges on CCP and MDC, which…

-

Erie Ins. Exchange v. Bristol: SOL on UM claims begins to run at refusal to arbitrate

Written by

on

On July 22, 2005, Mr. Bristol was injured when he was struck in a hit and run accident within the scope of his employment in Upper Dublin Township (childhood home…

-

In re Roca, In re Segal: No, we can’t just ignore the Constitution

Written by

on

The Supreme Court of Pennsylvania is, perhaps, the most powerful state Supreme Court within its own jurisdiction. Given comprehensive power over all attorney discipline matters by the state Constitution, our…

-

Nextel v. Commonwealth: Uniformity Clause Bars Flat Cap for Taxes, but Statute is Severable

Written by

on

When paying corporate income tax in Pennsylvania, a corporation is permitted to carry over a net loss from the previous year to reduce the current tax year’s taxable income. However,…