Author: Joel Ready

-

Com v. Crispell: PCRA Petitions may be amended to add new claims, even if the new claims fall outside of the “one year” rule

Written by

on

In an otherwise mundane PCRA affirmance, the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania ruled unanimously that a PCRA petitioner may move to amend his petition to add an additional claim, even if…

-

Com v. Wilmer: Community Caretaking exception to warrant requirement lasts until officer is done rendering assistance

Written by

on

A party at a sorority house led to a drunk college kid on the roof of the house, stumbling about, looking as though he were about to fall off the…

-

Danganan v. Guardian Protective Services: UTPCPL violation need not be in Pennsylvania

Written by

on

The Pennsylvania Supreme Court ruled unanimously in Danganan v. Guardian Protective Services that a violation of the Unfair Trade Practices Consumer Protection Law need not have occurred in Pennsylvania to…

-

Com v. Fulton: Warrantless Cell Phone searches violate both Constitutions

Written by

on

In a relatively-unsurprising re-affirmation of recent SCOTUS caselaw, the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania ruled 6-0 in Commonwealth v. Fulton that a warrantless search of a cell phone is unconstitutional and…

-

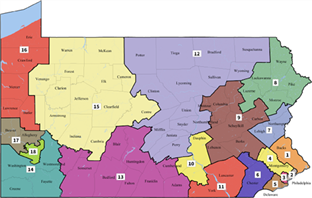

Federal Block to Gerrymandering Roundup 2-26-18

Written by

on

The fight over SCOPA’s gerrymandering decision continues. SCOTUS denied cert from the first decision, but now the issuance of the map is being challenged. Lyle Denniston of SCOTUSblog fame discusses…

-

League of Women Voters v. Commonwealth: The “Free and Equal Elections” Clause Prohibits Gerrymandering

Written by

on

EDIT: The map has been released as promised by the Court, along with a brief opinion on February 19, re-outlining the views of the Court. We have included it here…

-

Com v. Yong: Collective Knowledge Doctrine Affirmed

Written by

on

When two police officers independently have the information necessary to constitute probable cause, but they have not communicated these facts to each other, is the arrest of the defendant constitutional?…

-

Com v. DiMatteo: PCRA petitioner entitled to new sentence where SCOTUS change occurred before his sentence was final

Written by

on

Commonwealth v. DiMatteo resolves an obscure overlap in sentencing rules in Pennsylvania, confirming that a Defendant is entitled to resentencing where he was not sentenced on his open plea before…

-

Shearer v. Hafer: Interlocutory Appeal unavailable for civil pretrial dispute over right to counsel at psychological examination

Written by

on

In Shearer v. Hafer, the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania rules 6-1 that an interlocutory appeal was not appropriate in a pretrial discovery dispute over whether a plaintiff has the right…

-

Com v. VanDivner: Three Part Miller Test Establishes Sanity for Death Penalty

Written by

on

The Supreme Court of Pennsylvania ruled 6-0 in Commonwealth v. VanDivner that a defendant whose intellectual impairments interfere with his ability to cognitively adapt is mentally incompetent as regards the…