League of Women Voters v. Commonwealth: The “Free and Equal Elections” Clause Prohibits Gerrymandering

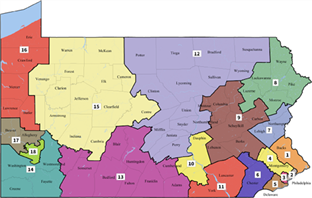

EDIT: The map has been released as promised by the Court, along with a brief opinion on February 19, re-outlining the views of the Court. We have included it here for ease of reference.

Ever since the Pennsylvania Supreme Court issued an expedited order in League of Women Voters v. Commonwealth, ordering the Commonwealth Court to proceed with discovery and findings of fact, many have speculated as to whether the Court would really rush out in front of the Supreme Court of the United States on the issue of gerrymandering and issue a decision attempting to proscribe the practice. In January, the Court not only did so, but in a 5-2 decision, required the legislature and governor to come to terms on a new congressional map before this year’s primary elections. The Court also ruled that Pennsylvania’s current congressional map violates the “Free and Equal Elections” clause in Article I, section 5 of the Pennsylvania Constitution.

Gerrymandering has a long and defiant history in the political systems of the United States—indeed, the practice is named after one of our founding fathers, who himself was hardly its first practitioner. Scholars, politicians and courts have proposed a number of solutions, but to date, none has proven to be particularly successful in curtailing the practice. Some argue that gerrymandering is the inescapable result of the political system, and that the power to draw lines is the natural spoil of the sport.

The Supreme Court of Pennsylvania’s opinion may be the most aggressive ever issued on gerrymandering, and it has sparked a political battle between the branches of the Commonwealth’s government. From the perspective of a judiciary-watcher, the case—and this opinion—have been entertaining. Not only has the case drawn national press attention, but it has invoked the more obscure tools of Pennsylvania’s flexible appellate judiciary, relied on the precedence of Pennsylvania’s constitution, fleshed out an Article I right that has lain dormant until now, highlighted the uniqueness of Pennsylvania’s federalist structure, and tested the limits of SCOPA’s powerful jurisdiction. This may be one of the greatest test of SCOPA’s power in the Pennsylvania political structure to date. Only one other state (Alaska) has ever found protections against gerrymandering in a state constitution, and Pennsylvania takes an enormous step in this area of law in holding that the congressional map “clearly, plainly and palpably violates the Pennsylvania Constitution.”

Majority by Todd: Districts must be compact, contiguous, and maintain the integrity of political subdivisions

In her 5-2 majority opinion, Justice Todd holds that Article I, section 5’s “free and equal elections” clause requires that the districts drawn by the legislature be 1) compact, 2) contiguous, and 3) maintain the integrity of political subdivisions. “Our founding document is the ancestor, not the offspring, of the federal Constitution,” the Court explains, which is significant in part because the traditional grounds for federal suits against state gerrymandering are grounded in the 14th Amendment—written long after the Pennsylvania Constitution’s Article I.

The provision at issue here reads as follows: “Elections shall be free and equal; and no power, civil or military, shall at any time interfere to prevent the free exercise of the right of suffrage.”

The Court delves into some of the most notable scholarship on the Pennsylvania Constitution’s development, finding that the “free and equal” provision was a response to the restrictions on the right of political minorities to vote, and that an election is not free and equal if individuals’ votes are targeted for dilution for political purposes. Such targeting robs the voter of his voice, and is antithetical to the democratic process.

The Court includes a great deal of discussion on the scientific and mathematical model findings of several expert witnesses, which support the Court’s ultimate ruling that this plan fails to satisfy the three overarching goals of the free and equal elections clause.

Finally, the Court gives a defense of its decision to rewrite the congressional map if the democrat Governor finds the Republican legislature’s plan unacceptable (which happened yesterday). The Court cites proudly to a Scalia decision from SCOTUS in Growe v. Emison, 507 U.S. 25 (1993), which ruled that federal courts should exercise Pullman abstention where a state court was redistricting the legislative map in an attempt to comply with federal law. (Scalia also called this a “highly political task” in that same opinion—the Court spends relatively little time in this opinion on justiciability or political question doctrine, which have traditionally prevented these suits).

SCOPA also argues that its powers derive from the legislative codification of SCOPA’s King’s Bench authority (SCOPA may “enter a final order or otherwise cause right and justice to be done.” 42 Pa.C.S. § 726). Of course, whether this King’s Bench authority allows the Court to usurp a traditional legislative function is a somewhat different question, which the Court does not address.

Concurrence by Baer: These criteria have no basis in the Constitution

Justice Baer concurs in the result, but would have waited to order a new map until after the primaries. Baer alleges that the lack of time to formulate a new map may even represent due process concerns for the parties to the case. He also has concerns about the clarity of the criteria developed by the Court—criteria which have no basis in the text of the Constitution. “I am unwilling to engraft into the Pennsylvania Constitution criteria for the drawing of congressional districts when the framers chose not to include such provisions despite unquestionably being aware of both the General Assembly’s responsibility for congressional redistricting and the dangers of gerrymandering. It is not this Court’s role to instruct the Legislature as to the ‘manner of holding elections,’ including the relative weight of districting criteria.”

Dissent by Saylor: improvident use of extraordinary jurisdiction

Chief Justice Saylor dissents, arguing that the Court should have awaited the “anticipated guidance from the Supreme Court of the United States,” particularly in light of how long the challengers waited to challenge the 2011 congressional map. The Chief Justice views the matter as inherently political, and would leave greater deference to the political branches.

Saylor also argues there is no “right to an equally effective power of voters in elections,” and that a voter’s diluted vote is part of the democratic process. Citing to a SCOTUS concurrence by Justice O’Connor, Saylor suggests that the “prophylactic” rule created here could have a chilling effect on even legitimate considerations (such as giving racial minorities greater pull in elections). Saylor also notes that the power to draw districts is left by the Federal Constitution’s Article I, section 4, to the legislatures of the states.

Dissent by Mundy: Stare Decisis and lack of constitutional mandate compel a different result

Justice Mundy dissents, arguing that the state constitution provides no clear guidance on how congressional maps are to be created, and criticizing the Court for “these vague judicially-created ‘neutral criteria,’” which “are now the guideposts against which all future congressional redistricting maps will be evaluated, with this Court as the final arbiter of what constitutes too partisan an influence.” Mundy also points to Erfer v. Com, 568 Pa. 128 (2002), in which the Court had previously considered and declined arguments to rule that gerrymandering violated the state constitution. Justice Mundy also discusses the SCOTUS caselaw cited by the majority, discussing how none of these cases dealt with the elections clause of the Federal Constitution’s Article I, section 4.

Conclusion: The political dispute becomes legal; but will the legal become political?

To say there are differing opinions on the validity of the Court’s judgment here is an understatement. The longshot appeal to SCOTUS—denied on February 5—argued that SCOPA had usurped the role delegated to the legislature by the Federal Constitution in Article I, section 4. The argument is that the Federal Constitution gives to certain branches of the state government specific jobs to do which may not be reviewed or impinged by other branches of the state government in order to ensure that certain necessary tasks within our federal system are left outside of state politics. If you recall, this was the argument embraced by a concurrence in Bush v. Gore in overruling a state court’s interpretation of its own laws, and instead accepting the state legislature’s prescribed process for vote counting. This argument may yet come back, depending on how SCOPA draws the congressional map.

But the biggest gripe which opponents of the decision have is that the Court has entered the political fray and rendered political disagreements justiciable. There will be hew and cry when a democratic map is upheld, or vice versa, and there will never be peace. The Court’s bold move may usher in calls for reining in the Court’s power, or even for a constitutional convention. When the political becomes legal, there is a danger that the legal will become political, subject to whims and passions. Law is a science, or so we lawyers like to think, separate and apart from the politicians’ arts. Now SCOTUS will have its turn; will its ruling be as bold? Or will SCOTUS dodge again on justiciability grounds? With League of Women Voters, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court takes a bold step into the fray. History will judge whether the step was wise or ill-considered.

Read More