Category: Constitutional Provisions

-

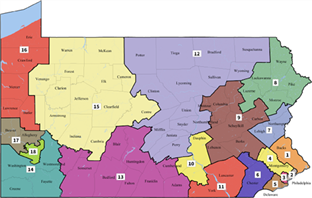

League of Women Voters v. Commonwealth: The “Free and Equal Elections” Clause Prohibits Gerrymandering

Written by

on

EDIT: The map has been released as promised by the Court, along with a brief opinion on February 19, re-outlining the views of the Court. We have included it here…

-

League of Women Voters v. Com: Congressional Map Violates PA Constitution

Written by

on

The Supreme Court of Pennsylvania decided today in a 4-3 per curiam decision that the congressional map drawn by the General Assembly is too partisan, and must be stricken because…

-

Scarnati v. Wolf: Press Releases aren’t “Proclamations”

Written by

on

In Scarnati v. Wolf, the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania rules 6-1 that a press release does not satisfy the Pennsylvania Constitution’s requirement of veto by proclamation under Article IV, Section…

-

In re Roca, In re Segal: No, we can’t just ignore the Constitution

Written by

on

The Supreme Court of Pennsylvania is, perhaps, the most powerful state Supreme Court within its own jurisdiction. Given comprehensive power over all attorney discipline matters by the state Constitution, our…

-

Nextel v. Commonwealth: Uniformity Clause Bars Flat Cap for Taxes, but Statute is Severable

Written by

on

When paying corporate income tax in Pennsylvania, a corporation is permitted to carry over a net loss from the previous year to reduce the current tax year’s taxable income. However,…

-

Com v. Shabezz: Automatic standing in Pennsylvania to challenge unconstitutional searches

Written by

on

Saleem Shabezz was observed by a policeman in a McDonald’s Parking Lot—a “hot zone,” known for drug deals by the police in Philadelphia (always a great place to find hot ‘zones).…

-

Villani v. Seibert: Dragonetti Statute Does Not Violate Separation of Powers; But We’re Leaving the Door Open

Written by

on

Civil lawyers know—and may even fear—the threat of a Dragonetti action. The draconian name accurately depicts one of the few times in law that a lawyer can subsequently be…

-

Pittman v. Pa. Bd. of Probation and Parole: Board Abused its Discretion by Failing to Use Discretion

Written by

on

The Parole Violation statute requires the Board of Probation and Parole to use its discretion when considering whether to credit “time at liberty on parole” to a convicted parole violator’s…

-

D.P. v. G.J.P.: Mere separation of parents is insufficient grounds to give grandparents standing to force custody dispute

Written by

on

The fourteenth amendment’s due process clause requires “that the custody, care and nurture of the child reside first in the parents,” (quoting Prince v. Mass, 321 U.S. 158, 166 (1944)),…

-

Cortes v. Sprague: Ambiguous Ballot Question Splits the Court

Written by

on

Sprague v. Cortes lined up some of the most notable names in Pennsylvania law against the Secretary of State over a question fundamental to the current and future composition of…